|

With

turnout in the UK General Election of 2001 back to

the levels of 1918, and the richest man in Italy

being elected Prime Minister of his country only a

couple of weeks before, it was fitting that Channel

Four in the UK was running a series of TV programmes

called 'Politics Isn't Working' during the UK

General Election. A faltering of democracy can be

seen across most of the developed world.

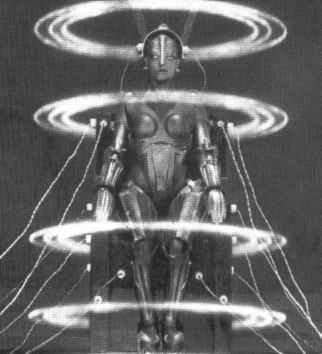

Something is clearly wrong. At other such depressing historical moments, critics have claimed to detect the symptoms of social pathology in the mass culture of their contemporaries. Siegfried Kracauer, a left-wing German, pioneered this sort of cultural psycho-analysis in surveying German cinema during the doomed Weimar Republic in his book From Caligari to Hitler- A Psychological History of the German Film (1947). Many have since penned articles at different times addressing instances of alleged social pathology in particular societies, sub-cultures and their mass culture. Eric Rhode in his A history of the cinema - from its origins to 1973 (1976) tried to psycho-analyse most of the last psycho-pathological century. More convincingly, Robin Wood was sharper focused in his impressive Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan (1986). At the beginning of our new century we can begin to get a better grasp of the real dynamics with which such critics were struggling. Such writers argued that psychological dynamics must be given such serious weight because the explanations put forward by historians and sociological writers had not seemed to fit the bill. As far as this goes it was justified. However, should sociological explanation get a more convincing grasp on the dynamics of the last century, the arguments of the Kracauers, the Rhodes and even the Robin Woods fade. Metropolis It was on the strength of his blockbuster Metropolis (1926), that the director Fritz Lang was offered prominence in the Nazi film world. Goebbells told him that Hitler and himself greatly admired the film, set in a mega-city of the future. Metropolis has been much admired since, and many film-makers have made versions of their own. Jean-Luc Godard's Alphaville (1965), George Lucas THX1138 (1970), Soylent Green (1973), Bladerunner (1982) and Brazil (1985) can be seen as merely the most eminent.

The hero of Metropolis however, is widely taken for a fool by many viewers. Even in 1926, many must have been irritated by Freder. For some viewers perhaps the film prompts them to reject the flinching and compromising that Kracauer himself rejects in Lang's 'hero'. Many of Lang's other films do allow the audience to either reject or sympathise with the films' heroes and this has often been written about by other critics. This alone undermines any credence one can put in Siegfried Kracauer's dogmatic diagnosis of Weimar cinema.

Lang's World

Most of the rest of Europe was then still living in the countryside and the villages. England and Wales led the world in urbanization. Already by the census of 1851, more of the population of England and Wales lived under what were called urban district councils than were left in the rural districts. Historians would agree that Germany was the next most urbanised major European power in the late nineteenth century. Urban in charge? Until the United Nations began to co-ordinate the measurement of development in the 1950s and 1960s, countries did not have to work out any criteria for what the urban was. Because Germany was formed from a mosaic of smaller states, German statistics had been particularly disjointed. While northern Germany had some of Europe's most massive cities (Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne), it is possible to over-estimate how urban the population of Germany actually was in 1900. Some writers have argued that Germans had mostly 'graduated' to urban life by 1900. This was probably wishful thinking on the part of the urban progressive elite. (Kracauer's own Germanised surname indicated a long history in urbanity, in Poland's ancient capital of Krakow.) By contrast, Hitler got proportionately more votes in rural than in urban Germany. This is often forgotten when the iconography of the historical newsreels is of urban unemployment being the backdrop to the storm trooper (though the Nazis' own iconography is distinctly more Sound of Music rustic). Hitler got his highest share of the vote in the rural protestant area called Schleswig-Holstein. This province had been grabbed by expanding Prussia in 1864. Resentment against rule by what was described as the 'Urban Prussian State' and later the 'Urban Jewish State' quickly set in. Schleswig-Holstein was electing anti-semitic representatives even before 1900. The Metropolis already was the object of fear and loathing. Rural backlash It was not just Hitler who marshaled his votes in rural Germany. So did the right wing and catholic parties whom he needed to allow the parliamentary surrender to dictatorship in 1933. The urban left, like Kracauer, under-estimated the political weight of rural Germany in 1933, in a way that more down to earth people did not. Perhaps one cannot safely say that anywhere is predominantly urban just because the census measure indicates 51%. Maybe 60% may be taken to be a more secure margin? Or even 66 %. Weimar Germany however was too evenly balanced between urban and rural for there not to have been a clash. But this did not then register with the metropolitan and cosmopolitan intelligentsia. The land that was Weimar had been only 50 % urban in population as war broke out in 1914 and only became 60 % urbanized around the fateful 1933. Rural Germany still had that weight of numbers, voters (and even conscripts) and so much else to seek to resist the politicians of the urban and especially the urban intelligentsia.(It all boiled down to the price of food in the end). It was this social polarization, - intensified with the economic crash of 1929, to which Metropolis contributed its hardly very measured comment upon where society/modernization was going. However many readings of the film there might be, the film ends without showing anything very hopeful in its images of the urban future. Artists have tended to make such bleak contributions to the consideration of urbanisation. When England was on this brink, Charles Dickens erupted onto the scene with a representation of the urban England that has endured ever since. In many ways Dickens did for urbanization with the written word what Lang's iconography did for twentieth century manifestations. These contributions must have some weight at a point where society is evenly split between people living (or surviving) in towns and cities, and the people in the countryside facing an immanent prospect of everything soon being geared towards the needs of the impending or looming majority. When a society is passing the point that makes it a majority urban one, (51:49) a many layered revolution will likely be underway. That innovations in literature and iconography should be thrown up, is hardly surprising. Now that we are able to look back over the remaining majority of the Twentieth Century since 1933, the importance of the transition point between urban and rural numerical dominance can be much better appreciated (if not understood). It is the declining rural society that almost always is better able to unite and assert itself. It normally supports a political upheaval that will be denounced by opinion in urban cosmopolitan circles as backward looking. In Weimar Germany, cinema (and METROPOLIS in particular) were really part of that rural backlash! Twentieth Century clash In these comments we have been discussing a European society with a western Christian history in the first third of the last century. However, in the last third of the century, similar social crisis could be seen in the societies with an Islamic heritage. Iran's population hit the 50:50 crisis in 1980, and the Shah was displaced by Islamic revolution. Other tremors seemed to herald further such shocks across the similarly split territories of the former Ottoman Turkish empire in the 1980s as the new Islamic politics arose. Then with the 1990s, the catholic and orthodox hereditary christian peoples in Yugoslavia abruptly embarked on a land-grab, the style of which recalled the Hitler era and not merely in the rural dynamic and weight that drove it. However, we cannot leave even such a brief consideration of Weimar cinema without saying something about another iconography it threw up. The Gothic that first appeared in Weimar cinema was a vicious attack on the crumbling rural social order. Its iconography was created in such films as The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1919) and Nosferatu (1922). This Gothic was adapted by Hollywood, above all in reworking the vampire theme. Although many critics have wrapped the vampire in all sorts of Freudian theory, he was always a rural aristocrat terrorizing and abusing the lower orders. That abuse always implied a sexual element for good measure. This attack on rural Europe was considered an important part of the appeal of the Gothic Horror among the European ethnicities from which the American audience was then in large part drawn. However, the emerging Gothic iconography plays a strange role in Metropolis. This is mainly in the representation of the scientist Rotwang and so serves here to compound the horror of the urban future. In passing comments on Kracauer, Metropolis and Fritz Lang, I hope to have set out how more sophisticated attention needs to be given to the social backdrop than social criticism inspired by the last century's involvement with Marx and Freud has so far required. As we embark upon this new century, mass culture is as much in need of analysis and evaluation as in the previous century. Further it is in the analysis of mass culture that new ways of understanding society can be found, should we free ourselves of the critical orthodoxies of the last century. The heirs of Marx and Freud no longer impress as they did. That these totems have collapsed has allowed us to seek out new ways of looking at the development of society and mass culture. NOTES Also see Andrew Lydon's Look Back In Disappointment. See Fritz Lang's Metropolis for links, images and references to this classic movie. Another excellent site that has loads of graphics, links and information is Verdantmetropolis For a profile of Fritz

Lang and his films go to www.filmfour.com

http://www.actualtests.com/exam-300-101.htm http://www.pass4sure.org/IBM/C4060-155.html http://www.test-king.com/vendor-IIBA.htm

|

The

iconography of this type of SF was invented by

Lang. Urbanisation and its iconography is not what

grabbed Kracauer's attention, however. It is the

politics and psychology that grabbed him. Two

elements in particular. Firstly, the hero brings

about a peace in the brutal class war (as Hitler

imagined he had) and secondly, the hero and

heroine are rebels who flinch from the very revolt

they embark upon. This flinching from the revolt,

is what Kracauer sees as sympathetic of too many

Germans who were opponents of Nazism. Such a film

fuels this political resignation. This resignation

is something endemic to Weimar films according to

Kracauer.

The

iconography of this type of SF was invented by

Lang. Urbanisation and its iconography is not what

grabbed Kracauer's attention, however. It is the

politics and psychology that grabbed him. Two

elements in particular. Firstly, the hero brings

about a peace in the brutal class war (as Hitler

imagined he had) and secondly, the hero and

heroine are rebels who flinch from the very revolt

they embark upon. This flinching from the revolt,

is what Kracauer sees as sympathetic of too many

Germans who were opponents of Nazism. Such a film

fuels this political resignation. This resignation

is something endemic to Weimar films according to

Kracauer.  Metropolis was promoted on

the basis of its images of our urban future.

However the opening shots of the film make clear

that even for the privileged of Metropolis

that urban future is an urban nightmare. Metropolis

makes darkness central to the iconography of the

urban future which has been taken up by most later

film-makers. Cinema took many of its narratives

and iconography from established art and

literature, but for the urban future there was

less to be borrowed than in most early film

ventures. So cinema had to break its own new

ground.

Metropolis was promoted on

the basis of its images of our urban future.

However the opening shots of the film make clear

that even for the privileged of Metropolis

that urban future is an urban nightmare. Metropolis

makes darkness central to the iconography of the

urban future which has been taken up by most later

film-makers. Cinema took many of its narratives

and iconography from established art and

literature, but for the urban future there was

less to be borrowed than in most early film

ventures. So cinema had to break its own new

ground.  Fritz

Lang had to do this at a time when there was a lot

less of the urban around than there would be when

he died in 1976. Lang was an Austrian. When he was

born in 1890, most of the subjects of his Emperor

still lived in villages and rural settlements.

However, the rump Austria that would in 1918

become the Austrian Republic was already in 1890

on the brink of becoming majority urban in

population. (Austrian statistics suggest it did so

in 1895) This Austria was one of the most

urbanized corners of Europe. By the time Lang made

Metropolis, 30 % of the Austrian population

was all in the one city - the Vienna in which he

was born. It should be remembered that London and

Paris were never more than 16 % of their

respective national populations. Lang's original

boyhood ambition in Vienna was to be an architect.

Fritz

Lang had to do this at a time when there was a lot

less of the urban around than there would be when

he died in 1976. Lang was an Austrian. When he was

born in 1890, most of the subjects of his Emperor

still lived in villages and rural settlements.

However, the rump Austria that would in 1918

become the Austrian Republic was already in 1890

on the brink of becoming majority urban in

population. (Austrian statistics suggest it did so

in 1895) This Austria was one of the most

urbanized corners of Europe. By the time Lang made

Metropolis, 30 % of the Austrian population

was all in the one city - the Vienna in which he

was born. It should be remembered that London and

Paris were never more than 16 % of their

respective national populations. Lang's original

boyhood ambition in Vienna was to be an architect.